By John Schauer

Way back in the day (I’m talking late 1960s) when I was a music major at Northwestern University and we were required to attend a certain number of student recitals each semester, I sat through more than my share of solo piano performances. The programming seemed to follow a formula: virtually every one began with something from the 18th century, usually something by Bach, Handel, or Scarlatti (all three of whom, through some cosmic coincidence, were born in the same year, 1685). I suppose they all wanted to show their stylistic versatility, but the practice has very old roots. After Franz Liszt popularized the solo piano recital in the 19th century, he routinely included pieces that were composed before the invention of the piano, when the king of solo keyboard instruments was the harpsichord. In a nutshell, the difference between the two instruments is that a harpsichord plucks the strings inside, whereas the piano strikes them. And because of this action, a piano can reproduce a whole range of dynamics simply from the player’s touch: the harder you hit the keys, the harder the hammer hits the string and the louder the tone is. The harpsichord has its own arsenal of tonal tricks, but this isn’t one of them.

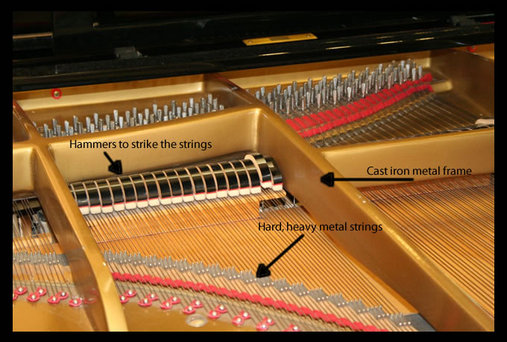

Inside of a Piano

Inside of a Piano Inside of a Harpsichord

Inside of a Harpsichord

(images from mrandersonsmusic.weebly.com/)

Because I was a music history student and still very young, I chafed at this appropriation of harpsichord music by pianists—especially since I was studying harpsichord—and it seemed rather obvious to me that one ought to perform music on the instrument for which it was composed. This was the bedrock assumption of the “original instrument” school of “authentic” performance practice, which was just beginning to go mainstream at the time and which today dominates the field of Baroque music performance. What I’ve learned since then, however, is that the whole subject is far more complex than it first seemed to me.

Take the three piano programs that will be presented in Bennett Gordon Hall on September 4, 5, and 6. On the first, Dmitri Levkovich will perform Bach’s Concerto nach italienischem Gusto, or, as it is commonly called, the “Italian Concerto.” Hearing this piece on the piano in my student days really got me up on my high horse, since it is a piece I learned and performed on harpsichord back then, but today I am a bit more humble about it, because in the intervening decades, the “original instrument” crowd became increasingly dogmatic. Now they not only expect the piece to be performed on the harpsichord, but they expect to hear it on a harpsichord that is a strict replica of a harpsichord from Bach’s time. It would be to their dismay that the instrument I performed on was what has become known as a “revival” harpsichord, which includes various accoutrements that were not available to Bach, in particular pedals that enable one to change registers—different sets of strings that have different sounds and allow a greater variety of tone than an “authentic” harpsichord. This was one of the “improvements” made to the instrument by Wanda Landowska, the legendary performer who more than anyone else was responsible for bringing harpsichords out of museums and onto concert stages. It’s an improvement I wouldn’t want to be without, but I may be a dying breed. About six years ago, Northwestern decided to get rid of an instrument it considered too out of fashion. But their loss became my gain, as that very instrument now sits in my dining room.

The subject becomes ever more complex as we progress through music history; on September 5, Ingolf Wunder will perform sonatas by Haydn and Beethoven. It’s generally accepted that these works were intended for the piano, but just as in the case of the harpsichord, pianos have evolved and changed in the more than 300 years since the instrument was invented. In fact, satisfying the purists these days requires having a whole fleet of pianos to reflect the changes made to the instrument during Beethoven’s lifetime. And muddying the waters further is the fact that the harpsichord had not completely disappeared during the times Haydn and Beethoven lived. Haydn’s earliest sonatas were clearly intended for the harpsichord, and even Beethoven published some of his sonatas “for harpsichord or piano”—among them such staples of the repertoire as his “Moonlight” and “Pathetique” Sonatas! I’ve never heard those works played on a harpsichord, and some have argued that the only reason he published them that way was to maximize music sales, but I think, more to the point, he wanted his music played and heard on whatever instrument was on hand. No one in the early 19th century would have purchased sheet music and then decided they couldn’t play it after all since they only owned a harpsichord. This notion of performing something exactly the way the composer would is a relatively recent development in the world of music, so in actuality the whole business of insisting upon an “authentic” performance isn’t really “authentic” at all.

Simon Savoy’s recital on September 6 points this up with his inclusion of a sonata by Domenico Scarlatti. Today it’s generally assumed that the more than 550 sonatas he composed were meant for the harpsichord, but historical evidence suggests Scarlatti himself was familiar with the early piano (or fortepiano as the earliest models are called today). And they have regularly been used as showpieces of technique and artistry by pianists on more modern models, from Franz Liszt to Vladimir Horowitz, who famously recorded an entire album of them to dazzling effect, so there is ample precedent for the practice. Today they are frequently heard on piano, as virtually all of the harpsichord literature is. So I say, sit back, relax, and enjoy the music. As a collegiate colleague of mine once said, purists don’t really like music; they’re only interested in hardware.